Sleep

The Biology of Sleep: Understanding the Science Behind the Night's Rest

Sleep. We all know it, we all do it, some love it and others hate it. But finding a clear definition is not so easy. Because of its complexity, most definitions amount to a description of the observable effects of sleep. By doing so, we might come up with the following description: sleep is a natural, periodic and reversible state of reduced responsiveness to external stimuli, marked by the absence of wakefulness and a loss of consciousness of our surroundings, that is accompanied by complex and predictable changes to our physiology.

Sleep is a fundamental aspect of human health. Yet it is an often overlooked component of our mental, physical and emotional wellbeing. Understanding the importance of quality sleep will help you appreciate why it is essential for maintaining overall health and vitality. Sleep is not merely a passive state of rest but rather a dynamic process that affects nearly every system in the body.

The Biology of Sleep: What Drives the Urge to Sleep?

Sleep is regulated by two primary processes: the circadian rhythm and sleep homeostasis.

The circadian rhythm is a roughly 24-hour cycle that governs many physiological processes, including the sleep-wake cycle. This internal "biological clock" is influenced by external cues, the most potent being light. The central regulator of circadian rhythm is located in the hypothalamus, a region of the brain that functions to regulate body temperature, some metabolic processes, and the autonomic nervous system. It responds to light signals from the retina, signaling to the brain and body when it is time to be awake or asleep. The hormone melatonin, produced by the pineal gland, facilitates signaling the body that it is time to prepare for sleep. Melatonin levels rise in the evening, peak during the night, and decline in the morning as light exposure increases, helping to align sleep patterns with the external environment.

Sleep homeostasis, often referred to as the sleep-wake balance, is the body's way of ensuring that it gets enough sleep. The longer you are awake, the stronger the drive to sleep becomes. This process is driven by the accumulation of adenosine, a neurotransmitter that builds up in the brain during wakefulness. Adenosine is an integral part of our body’s energy system, as it is a building block of ATP, a molecule essential to energy production. During the metabolism of ATP during the day, more and more adenosine will bind to receptors in the brain. As adenosine levels rise, so does the pressure to sleep. Caffeine, a common stimulant, works by blocking adenosine receptors, temporarily reducing the perception of sleepiness.

The Structure of Sleep: A Journey Through the Night

Figure 1: Brain waves during the stages of sleep

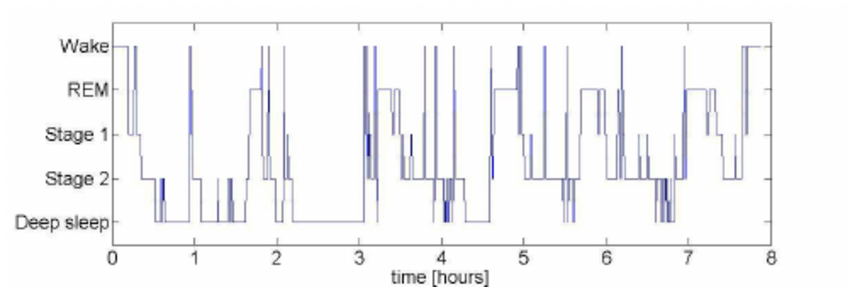

Sleep is not a uniform state but is composed of cycles, phases and stages. A typical night of sleep consists of four to six sleep cycles, each lasting about 90 minutes. A complete cycle consists of two phases: Non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM) sleep and Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep. The non-REM phase can be further divided into three stages – N1, N2 and N3 – each playing a unique role in the restorative processes of sleep.

N1 is the lightest stage of sleep, often lasting just a few minutes. It serves as the transition from wakefulness to sleep. During this stage, the body begins to relax, and brain activity slows down. In Stage 1 sleep people can be easily awakened and might not even realize they were asleep.

N2 marks the onset of true sleep. It is characterized by a further reduction in heart rate and body temperature, and the brain begins to produce specific brain waves. Stage 2 sleep makes up a large portion of the sleep cycle and is thought to be essential for cognitive functions such as memory consolidation.

N3, also known as slow-wave sleep or deep sleep, is the most restorative stage of sleep. During this phase, brain activity slows, and it becomes more difficult to wake someone. This stage is crucial for physical repair, growth, and immune function.

REM sleep, aptly named for the rapid eye movements that occur during this stage, is when most dreaming takes place. Unlike NREM sleep, REM sleep is characterized by increased brain activity, similar to wakefulness, but with muscle atonia (paralysis), preventing the body from acting out dreams (without muscle atonia, imagine what could happen if you dreamt about being able to fly). REM sleep is associated with emotional regulation, learning, and memory consolidation. It also plays a role in the brain's ability to manage stress and mood. Interestingly, disruptions in REM sleep have been linked to various mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety.

Throughout the night, the proportion of the different phases and stages within a sleep cycle changes, as well as the duration of the sleep cycles themselves. Early on, a sleep cycle consists of a large amount of non-REM sleep and only few REM sleep moments. As the night progresses, the ratio of NREM and REM sleep changes favouring the occurrence of the REM phase. Progressing towards your natural point of restfulness, you will no longer be able to reach the deeper stages of NREM sleep. Your sleep cycles might shorten and you will spend more time near wakefulness. This will allow you to wake up more easily in the morning.

The Biology of Sleep Phases: More Than Just Rest

Each phase of sleep serves a distinct and vital function. Understanding these functions can shed a light on why sleep is so essential for health.

Memory consolidation is the process by which short-term memories are transformed into long-term memories. This process occurs primarily during sleep, especially during Stage 2 NREM and REM sleep. The brain's ability to reorganize and integrate new information is an underpinning of cognitive performance. Sleep deprivation can impair the brain’s ability to consolidate memories, leading to difficulties in learning and memory recall. This is why a good night's sleep is often linked to better learning and memory retention. So even if you feel like pulling an allnighter before an exam helps you retain information, forfeiting your sleep inhibits the transition of information from short-term to long-term memory.

REM sleep is particularly important for emotional health. During this phase, the brain processes emotional experiences and helps regulate mood. This stage of sleep is characterized by heightened brain activity and dreaming, which allow the brain to work through and make sense of emotional events. It helps to diminish the emotional intensity of memories by separating the emotional content from the memory itself. Lack of sleep, especially insufficient REM sleep, can have significant consequences for emotional health. Sleep deprivation has been linked to increased emotional reactivity, irritability, and a heightened risk of developing mood disorders such as anxiety and depression. Chronic sleep loss can also impair the brain’s ability to cope with stress, leading to a vicious cycle where poor sleep exacerbates emotional difficulties, which in turn further disrupts sleep.

Deep sleep (Stage 3 NREM) is when the body engages in a variety of repair processes. For example, the pituitary gland releases growth hormone, which stimulates the regeneration of tissues and the repair of muscle fibers that may have been damaged during the day. The body also increases the production of cytokines, proteins that help fight infection, inflammation, and stress. Insufficient sleep can disrupt the restorative processes, leading to a range of health issues. Chronic sleep deprivation has been linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, weakened immune function, slower wound healing, and a higher likelihood of developing chronic conditions such as diabetes and obesity. The body's inability to properly repair and restore itself during sleep can accelerate the aging process and increase vulnerability to illness.

Sleep also affects metabolic health, influencing everything from appetite regulation to glucose metabolism. Glucose homeostasis, the balance of insulin and glucose in the body, is regulated increasing our sensitivity to insulin. Disruptions in sleep, particularly in deep sleep, can impair glucose metabolism and lead to insulin resistance, a precursor to type 2 diabetes. Sleep also act on the hormones that regulate appetite, such as ghrelin and leptin. Ghrelin, known as the “hunger hormone,” increases appetite, while leptin signals satiety, helping to regulate food intake. Sleep deprivation disrupts the balance between these hormones, leading to increased hunger and cravings, particularly for high-calorie, carbohydrate-rich foods.

Sleep is far more than a period of rest; it is a complex and dynamic process that plays a fundamental role in maintaining cognitive, emotional, physical, and metabolic health. They are just a few of the many functions that sleep serves. Understanding these functions underscores the importance of prioritizing sleep as a fundamental pillar of health and well-being.

Optimizing Sleep: The QQRT Framework

Having established the importance of sleep and some of the functions it serves, we might wonder how to get “better sleep”. The QQRT framework proposes four elements contributing to good sleep. Improving each of these aspects might prove useful in optimizing sleep and, consequently, health. The aspects are: Quality, Quantity, Regularity, and Timing.

Quality: Sleep quality refers to how well you sleep, which includes how quickly you fall asleep, how often you wake up during the night, and how refreshed you feel in the morning. High-quality sleep is uninterrupted and restorative. Poor sleep quality can lead to fatigue, irritability, and impaired cognitive function, even if the duration of sleep is adequate. To improve sleep quality, consider factors such as your sleep environment (e.g., a dark, quiet, and cool room), stress management, and what you do before bed. Watching a horror movie or doing a hard workout might increase your arousal state, taking away from your sleep quality. You can try to regulate your arousal by avoiding bright light (including screens), listening to easy-going music or doing a meditation routine.

Quantity: Sleep quantity is the total amount of sleep you get each night. Individual needs can vary, based on factors such as age, lifestyle or health conditions. Whereas babies can sleep for over 15 hours per day, some adults come by with only 5 hours of sleep. As a general number, a sleep duration of 7-9 hours seems to fit a majority of people. Interestingly, teenagers seem to be most unwilling to sacrifice wakefulness for sleep. However, during puberty, they undergo significant physical and neurological changes. The adolescent brain is still developing, particularly in areas responsible for decision-making, impulse control, and emotional regulation. One might argue that this developmental process requires additional sleep to support the brain's maturation and the complex changes occurring during this period.

Regularity: Regularity refers to maintaining a consistent sleep schedule, going to bed and waking up at the same time every day. Irregular sleep patterns, such as those caused by shift work or social jetlag (e.g. the difference between weekday and weekend sleep patterns), can disrupt the circadian rhythm. Having a consistent evening routine may provide useful in maintaining a regular sleep schedule. For example, having your evening meal around the same time every day, or incorporating a bedtime routine of brushing your teeth and going to the toilet might help signal your body that it’s time to go to bed.

Timing: Sleep timing relates to when you sleep, which is closely tied to your circadian rhythm and to the concept of “chronotype”. This refers to an individual's natural preference for being active at certain times of the day. Chronotype is typically categorized into two main types: morningness, colloquially named “morning larks”, and eveningness, or “evening owls”. Most people fall somewhere in between these extremes, exhibiting a flexible chronotype that can adapt to various schedules. Aligning your sleep with your natural circadian rhythm can enhance sleep quality and overall health. While you can adjust your sleep schedule to some extent, you cannot fundamentally change your chronotype. Your natural inclination towards being a morning or evening person is stable and largely genetic. Forcing an evening type to go to bed earlier might be counterproductive, as they will have difficulty falling asleep.

The elements of the QQRT framework—Quality, Quantity, Regularity, and Timing—are not isolated factors but are deeply interconnected, each influencing the others in significant ways. High-quality sleep supports sufficient sleep quantity, while consistent sleep patterns enhance both sleep quality and quantity by stabilizing the circadian rhythm. Proper sleep timing ensures that sleep occurs during the optimal period for restorative rest, further enhancing sleep quality and quantity.

Understanding the interconnectedness of these elements is crucial for optimizing sleep and, by extension, overall health and well-being. By focusing on improving each component of the QQRT framework, you can create a positive feedback loop that enhances your sleep experience, leading to better daytime energy, focus, and long-term health. Sleep is not a luxury but a vital component of a healthy lifestyle, and the QQRT framework offers a comprehensive approach to ensuring that sleep is as restorative and beneficial as possible.